Mark Steyn strikes again: in this opinion piece in the Telegraph, he reveals the primary result of a study from the University of Oslo about the emotional legacy of abortion versus miscarriage. The study, it seems, was small, comparing 40 women who had suffered miscarriages with 80 women who had had abortions, but the salient points ought to make anyone considering an abortion take notice: many women of both groups suffered emotional distress in the immediate aftermath of their pregnancy-ending event - 47.5% of women who had miscarried and 30% of women who had had abortions. But after six months, the percentage of women who had miscarried who continued to feel distress over their miscarriage had fallen to 22.5%, while the percentage of women who felt distress over their abortions had fallen much less, proportionately - to 25.7%. At five years after the event, less than 3% of women who had miscarried continued to be distressed.

Twenty percent of women who had had abortions were still distressed, five years afterward.

These figures are all from this article from BBC News; I have so far not turned up the original study. I wish I could. Was the women's distress self-reported, or inferred through questioning or a standardized test? Was it measured in degrees, or simply Booelian? But while the methodology is important, the apparent result says something to me about the nature of regret.

I have few, thankfully. Sometimes a choice between two courses has been decided for me by events, so that even if I might suspect that the road I didn't travel would have had more interesting scenery, I can't honestly regret that I took the other road - I perceived no choice. Sometimes I have indeed made a choice, and I have indeed spent time down the line wondering what might be different in my life if I had chosen the other course - but since I can see the life I have, and can't think of much in it that I would willingly give up, it's hard to regret any choice that led me to this place. Has my life been unusally blessed?

Well, I certainly think so, and as a superstitious Irishwoman I waste a good bit of mental energy wondering when the other shoe is going to drop. But really, if we're speaking of regret, I'd have to say that a regret presupposes that the difference in your life that you imagine if you had made a different choice would have been a positive difference. In other words, one in every five of the studied women who chose to end her pregnancy has concluded after five years of living with that decision that, no matter how difficult the prospect of having a child might have seemed back then, having that child now could have been better.

I'm reading a lot into a few isolated numbers. But think about it. Try to project yourself into your own future. It's nearly an impossible exercise, but the effort alone may at least ease your mind later.

Musings from somebody who ought to know better than to go shooting her mouth off, but does it anyway

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

The end of the world as we know it

Much is being made of the recent leak to the New York Times that the Bush administration authorized unwarranted (meaning "without-a-warrant" rather than "unnecessary") taps on international calls between certain individuals whose names or phone numbers had been learned through questioning of al Qaeda members or other al Qaeda-related intel. See here and here for two news reports on the story.

Out here in the blogosphere, there's a whole lot about the Fourth Amendment being thrown around. But let's review:

I am not a lawyer, nor a Constitutional scholar. (These facts are patent.) But to the extent that it matters in a mere private citizen, I am a strict constructionist. Yet I have no beef with the phone taps, as far as the facts are currently known. Because:

...and we are at war, a condition that has in the past required the chief executive to suspend the writ of habeus corpus (Lincoln), to undertake massive secret projects with budgets disguised under other line items (Roosevelt), to intern US citizens (also Roosevelt), among other temporary infringements of the widest exercise of civil liberties. Key here is the temporary nature of such infringements, and it's inherent in our system: until a president disbands Congress and calls off general elections (yes, I do recall that some were claiming before the 2004 elections that Bush would pull a real October surprise and do exactly that - my goodness, you people, get a hold of yourselves), there is no statute or order that cannot be considered "temporary." And bear in mind the word "unreasonable" in the Fourth: is it "unreasonable" to assume that a person who has been receiving calls from known members of al Qaeda, a hostile foreign group bent on the destruction of the United States among others, may be connected to them somehow? If it's reasonable, strict interpretation of the Amendment would seem to allow that person's virtual "papers" to be searched. So everyone take a deep breath.

The difficult part is remembering that we are actually at war. I suspect it's always been harder for us to remember this fact than for, say, Europe - at least since the War of 1812, the last time we saw a hostile foreign army on our mainland. So many of us have no personal experience of a real, bloody war - the kind of war the Soviet Union waged against Afghans, the kind of war Saddam Hussein waged against Kuwait, the kind of war that tore Vietnam in two until we graciously allowed the bad guys to stitch it back together without benefit of anesthesia. So many of us forget that it's not just the forces of nature that can cost hundreds of thousands, even millions of lives. Thank God, we in the United States have not seen so bloody a war on our own soil since the 1860s, but lest we doubt that it's possible, take note of the horror of Darfur, where credible sources put the number dead at 300,000 or more. Because at this moment in history, the really deadly conflicts all seem to be taking place in the Third World or thereabouts, we may foolishly conclude that we're somehow more "civilized"; but bear in mind that it was not long ago that the Soviet Union was in the business of killing in the millions, and while Stalin may not have been "our kind of people," he was most assuredly not one of the dressed-up savages some of us in the enlightened West may wishfully see in Africa and the Middle East.

No, he was a real monster. Something that George W. Bush demonstrably is not.

Out here in the blogosphere, there's a whole lot about the Fourth Amendment being thrown around. But let's review:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oaths or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

I am not a lawyer, nor a Constitutional scholar. (These facts are patent.) But to the extent that it matters in a mere private citizen, I am a strict constructionist. Yet I have no beef with the phone taps, as far as the facts are currently known. Because:

[from Article II, Section 1:] Before he enter on the Execution of his Office, he shall take the following Oath or Affirmation:

"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States."

Section 2 - Civilian Power over Military, Cabinet, Pardon Power, Appointments

The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States...

...and we are at war, a condition that has in the past required the chief executive to suspend the writ of habeus corpus (Lincoln), to undertake massive secret projects with budgets disguised under other line items (Roosevelt), to intern US citizens (also Roosevelt), among other temporary infringements of the widest exercise of civil liberties. Key here is the temporary nature of such infringements, and it's inherent in our system: until a president disbands Congress and calls off general elections (yes, I do recall that some were claiming before the 2004 elections that Bush would pull a real October surprise and do exactly that - my goodness, you people, get a hold of yourselves), there is no statute or order that cannot be considered "temporary." And bear in mind the word "unreasonable" in the Fourth: is it "unreasonable" to assume that a person who has been receiving calls from known members of al Qaeda, a hostile foreign group bent on the destruction of the United States among others, may be connected to them somehow? If it's reasonable, strict interpretation of the Amendment would seem to allow that person's virtual "papers" to be searched. So everyone take a deep breath.

The difficult part is remembering that we are actually at war. I suspect it's always been harder for us to remember this fact than for, say, Europe - at least since the War of 1812, the last time we saw a hostile foreign army on our mainland. So many of us have no personal experience of a real, bloody war - the kind of war the Soviet Union waged against Afghans, the kind of war Saddam Hussein waged against Kuwait, the kind of war that tore Vietnam in two until we graciously allowed the bad guys to stitch it back together without benefit of anesthesia. So many of us forget that it's not just the forces of nature that can cost hundreds of thousands, even millions of lives. Thank God, we in the United States have not seen so bloody a war on our own soil since the 1860s, but lest we doubt that it's possible, take note of the horror of Darfur, where credible sources put the number dead at 300,000 or more. Because at this moment in history, the really deadly conflicts all seem to be taking place in the Third World or thereabouts, we may foolishly conclude that we're somehow more "civilized"; but bear in mind that it was not long ago that the Soviet Union was in the business of killing in the millions, and while Stalin may not have been "our kind of people," he was most assuredly not one of the dressed-up savages some of us in the enlightened West may wishfully see in Africa and the Middle East.

No, he was a real monster. Something that George W. Bush demonstrably is not.

Wednesday, December 14, 2005

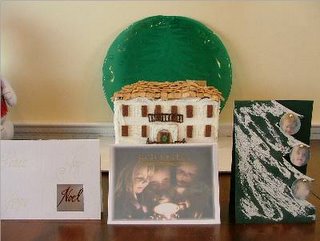

Christmas card blogging

About nine years ago, I started making my own Christmas cards. I blame my sister, who at that time was an ardent rubber-stamper; she started turning out cards of professional quality but personal soul, and I obviously couldn't let her do that without putting forth my own effort.

The above are the last three years' worth - this year's is the rightmost, last year's (my favorite, though the least work for me) in the middle, and the previous year's, which doesn't photograph as well - it's probably one of my prettiest stamp-only cards ever - on the left. Behind the cards is my fake gingerbread house, modeled on our actual house, with, yes, Golden Grahams for shingles. (The "fake" part is that I didn't make gingerbread; I glued innumerable pieces of graham cracker together with royal icing, mistakenly believing it'd be faster and easier than the all-gingerbread method. The house is indeed entirely edible, though by the time I let the kids eat it, it'll probably be so dusty that only a child would stoop to breaking off a hunk.)

A friend of ours, an architect by training whose creativity is beyond the ken of normal (wo)men, makes the most original dang Christmas cards imaginable. One year, the card cover was paper dolls of her entire family: color photos of them on glossy cardstock, all wearing red long underwear. Inside the card, she'd included a piece of regular-weight paper with elf constumes, with paper-doll-costume tabs, to fit the people and poses. Another year, the card was a snowglobe: her family posing in front of the Space Needle (this was in their, and our, Seattle days), with a small plastic zipper bag containing glitter "snow" somehow attached to it; the recipient put a little water in the bag and presto! A favorite of mine was the year she was pregnant with their first child; she wrapped a strand of white Christmas lights around her very pregnant belly and had her husband take a black and white picture of just that, then "colorized" (by hand - this was pre-Photo Shop-in-the-home) just the area of the glow. Beautiful! I aspire to her standards but have no hope of reaching them. Her cards are one of many things I look forward to at Christmas. Heaven help me if she ever decides it's too much work and hits Hallmark instead...

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

Life and death in San Quentin

This morning "Tookie" Williams was executed by the State of California for the crime of multiple murder. Some insisted that he was innocent, though

Evidence against him included "testimony from two of Williams' accomplices, ballistics evidence linking Williams' shotgun to the murders and testimony from four people that Williams had at different times confessed to one or both murders."

I am, as anyone reading this blog at the time of Terry Schindler Schiavo's death can see, a proponent of life even if the life in question has little or no apparent objective value. Life is precious and irreplaceable. That said, it does not follow that all life must be preserved at all costs. There are reasons to give up one's own life; there are reasons to take a life. My belief in the value of human life wouldn't make me hesitate for one second to kill (or, more likely, to try to kill - it's not something I have practice in) someone threatening my kids, for instance. It's also why I remain reluctantly on the side of maintaining a limited legal status for abortion, though I would like to see its limitations include (a) state-by-state decisions (that is, a rollback of Roe v. Wade) and (b) first-trimester legality only, except in cases where multiple, independent, "blind" reviews indicate that the mother's life, not simply her "health," are in danger if the pregnancy is allowed to continue. This is my personal wish list. I'm not at all satisfied with it, but there it stands for the moment.

Similarly, I recognize that the death penalty opens the door for innocent people to die. More broadly, any reasonable system of jurisprudence - that is, any system that allows evidence other than multiple unambivalent eye-witness accounts coupled with incontrovertible forensic evidence, for instance - opens the door for innocent people to be punished for crimes they didn't commit. The death penalty is more a symptom of that fact than a cause in itself. Such Has It Always Been. I believe there should be a very high standard of evidence for capital cases - of evidence rather than of legal argument; I don't like the thought of clearly guilty murderers "getting off on a technicality" (who does?). Mr. Williams, having been convicted on strong evidence of four cold-blooded murders, died today because his life is forfeit for those innocent lives, regardless of his later redemption (which did not include remorse, since he maintained all along that he was innocent himself).

All right. I have heard the argument that since Williams was a cofounder of the Crips, even if he was innocent of these four murders, he was certainly guilty of conspiracy to murder, that being one of the Crips' hobbies, and therefore deserved to die anyway. I can't buy that. What I do buy is that his original trial, with fresh and clear evidence including his own boasts, came to a just conclusion, and he deserved to die because he was guilty of what he was accused of.

A life has been ended at the hands of society. That life had intrinsic worth from beginning to end, but its owner freely chose to set his life in trade for some momentary pleasure or gratification or perceived need that resulted in four violent deaths at his hands. We have soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan who are setting their lives in trade for a chance at freedom and prosperity for millions of strangers abroad, and for the long-term safety of millions of strangers and a smaller number of loved ones at home. Their trade is a generous act; his was a selfish one. Their trade preserves and defends other lives; his ended at least four. Just as these soldiers choose their course with their eyes wide open, he apparently made that choice years ago, and just as some of these soldiers will have to give their lives in the trade they endorsed, he has given his. Life is precious, but it is not always paramount.

[w]itnesses at [his] trial said he boasted about the killings, stating "You should have heard the way he sounded when I shot him." Williams then made a growling noise and laughed for five to six minutes, according to the transcript that the governor referenced in his denial of clemency.

Evidence against him included "testimony from two of Williams' accomplices, ballistics evidence linking Williams' shotgun to the murders and testimony from four people that Williams had at different times confessed to one or both murders."

I am, as anyone reading this blog at the time of Terry Schindler Schiavo's death can see, a proponent of life even if the life in question has little or no apparent objective value. Life is precious and irreplaceable. That said, it does not follow that all life must be preserved at all costs. There are reasons to give up one's own life; there are reasons to take a life. My belief in the value of human life wouldn't make me hesitate for one second to kill (or, more likely, to try to kill - it's not something I have practice in) someone threatening my kids, for instance. It's also why I remain reluctantly on the side of maintaining a limited legal status for abortion, though I would like to see its limitations include (a) state-by-state decisions (that is, a rollback of Roe v. Wade) and (b) first-trimester legality only, except in cases where multiple, independent, "blind" reviews indicate that the mother's life, not simply her "health," are in danger if the pregnancy is allowed to continue. This is my personal wish list. I'm not at all satisfied with it, but there it stands for the moment.

Similarly, I recognize that the death penalty opens the door for innocent people to die. More broadly, any reasonable system of jurisprudence - that is, any system that allows evidence other than multiple unambivalent eye-witness accounts coupled with incontrovertible forensic evidence, for instance - opens the door for innocent people to be punished for crimes they didn't commit. The death penalty is more a symptom of that fact than a cause in itself. Such Has It Always Been. I believe there should be a very high standard of evidence for capital cases - of evidence rather than of legal argument; I don't like the thought of clearly guilty murderers "getting off on a technicality" (who does?). Mr. Williams, having been convicted on strong evidence of four cold-blooded murders, died today because his life is forfeit for those innocent lives, regardless of his later redemption (which did not include remorse, since he maintained all along that he was innocent himself).

All right. I have heard the argument that since Williams was a cofounder of the Crips, even if he was innocent of these four murders, he was certainly guilty of conspiracy to murder, that being one of the Crips' hobbies, and therefore deserved to die anyway. I can't buy that. What I do buy is that his original trial, with fresh and clear evidence including his own boasts, came to a just conclusion, and he deserved to die because he was guilty of what he was accused of.

A life has been ended at the hands of society. That life had intrinsic worth from beginning to end, but its owner freely chose to set his life in trade for some momentary pleasure or gratification or perceived need that resulted in four violent deaths at his hands. We have soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan who are setting their lives in trade for a chance at freedom and prosperity for millions of strangers abroad, and for the long-term safety of millions of strangers and a smaller number of loved ones at home. Their trade is a generous act; his was a selfish one. Their trade preserves and defends other lives; his ended at least four. Just as these soldiers choose their course with their eyes wide open, he apparently made that choice years ago, and just as some of these soldiers will have to give their lives in the trade they endorsed, he has given his. Life is precious, but it is not always paramount.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)