Musings from somebody who ought to know better than to go shooting her mouth off, but does it anyway

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

The nature of regret

Twenty percent of women who had had abortions were still distressed, five years afterward.

These figures are all from this article from BBC News; I have so far not turned up the original study. I wish I could. Was the women's distress self-reported, or inferred through questioning or a standardized test? Was it measured in degrees, or simply Booelian? But while the methodology is important, the apparent result says something to me about the nature of regret.

I have few, thankfully. Sometimes a choice between two courses has been decided for me by events, so that even if I might suspect that the road I didn't travel would have had more interesting scenery, I can't honestly regret that I took the other road - I perceived no choice. Sometimes I have indeed made a choice, and I have indeed spent time down the line wondering what might be different in my life if I had chosen the other course - but since I can see the life I have, and can't think of much in it that I would willingly give up, it's hard to regret any choice that led me to this place. Has my life been unusally blessed?

Well, I certainly think so, and as a superstitious Irishwoman I waste a good bit of mental energy wondering when the other shoe is going to drop. But really, if we're speaking of regret, I'd have to say that a regret presupposes that the difference in your life that you imagine if you had made a different choice would have been a positive difference. In other words, one in every five of the studied women who chose to end her pregnancy has concluded after five years of living with that decision that, no matter how difficult the prospect of having a child might have seemed back then, having that child now could have been better.

I'm reading a lot into a few isolated numbers. But think about it. Try to project yourself into your own future. It's nearly an impossible exercise, but the effort alone may at least ease your mind later.

The end of the world as we know it

Out here in the blogosphere, there's a whole lot about the Fourth Amendment being thrown around. But let's review:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oaths or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

I am not a lawyer, nor a Constitutional scholar. (These facts are patent.) But to the extent that it matters in a mere private citizen, I am a strict constructionist. Yet I have no beef with the phone taps, as far as the facts are currently known. Because:

[from Article II, Section 1:] Before he enter on the Execution of his Office, he shall take the following Oath or Affirmation:

"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States."

Section 2 - Civilian Power over Military, Cabinet, Pardon Power, Appointments

The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States...

...and we are at war, a condition that has in the past required the chief executive to suspend the writ of habeus corpus (Lincoln), to undertake massive secret projects with budgets disguised under other line items (Roosevelt), to intern US citizens (also Roosevelt), among other temporary infringements of the widest exercise of civil liberties. Key here is the temporary nature of such infringements, and it's inherent in our system: until a president disbands Congress and calls off general elections (yes, I do recall that some were claiming before the 2004 elections that Bush would pull a real October surprise and do exactly that - my goodness, you people, get a hold of yourselves), there is no statute or order that cannot be considered "temporary." And bear in mind the word "unreasonable" in the Fourth: is it "unreasonable" to assume that a person who has been receiving calls from known members of al Qaeda, a hostile foreign group bent on the destruction of the United States among others, may be connected to them somehow? If it's reasonable, strict interpretation of the Amendment would seem to allow that person's virtual "papers" to be searched. So everyone take a deep breath.

The difficult part is remembering that we are actually at war. I suspect it's always been harder for us to remember this fact than for, say, Europe - at least since the War of 1812, the last time we saw a hostile foreign army on our mainland. So many of us have no personal experience of a real, bloody war - the kind of war the Soviet Union waged against Afghans, the kind of war Saddam Hussein waged against Kuwait, the kind of war that tore Vietnam in two until we graciously allowed the bad guys to stitch it back together without benefit of anesthesia. So many of us forget that it's not just the forces of nature that can cost hundreds of thousands, even millions of lives. Thank God, we in the United States have not seen so bloody a war on our own soil since the 1860s, but lest we doubt that it's possible, take note of the horror of Darfur, where credible sources put the number dead at 300,000 or more. Because at this moment in history, the really deadly conflicts all seem to be taking place in the Third World or thereabouts, we may foolishly conclude that we're somehow more "civilized"; but bear in mind that it was not long ago that the Soviet Union was in the business of killing in the millions, and while Stalin may not have been "our kind of people," he was most assuredly not one of the dressed-up savages some of us in the enlightened West may wishfully see in Africa and the Middle East.

No, he was a real monster. Something that George W. Bush demonstrably is not.

Wednesday, December 14, 2005

Christmas card blogging

About nine years ago, I started making my own Christmas cards. I blame my sister, who at that time was an ardent rubber-stamper; she started turning out cards of professional quality but personal soul, and I obviously couldn't let her do that without putting forth my own effort.

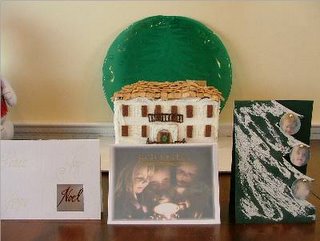

The above are the last three years' worth - this year's is the rightmost, last year's (my favorite, though the least work for me) in the middle, and the previous year's, which doesn't photograph as well - it's probably one of my prettiest stamp-only cards ever - on the left. Behind the cards is my fake gingerbread house, modeled on our actual house, with, yes, Golden Grahams for shingles. (The "fake" part is that I didn't make gingerbread; I glued innumerable pieces of graham cracker together with royal icing, mistakenly believing it'd be faster and easier than the all-gingerbread method. The house is indeed entirely edible, though by the time I let the kids eat it, it'll probably be so dusty that only a child would stoop to breaking off a hunk.)

A friend of ours, an architect by training whose creativity is beyond the ken of normal (wo)men, makes the most original dang Christmas cards imaginable. One year, the card cover was paper dolls of her entire family: color photos of them on glossy cardstock, all wearing red long underwear. Inside the card, she'd included a piece of regular-weight paper with elf constumes, with paper-doll-costume tabs, to fit the people and poses. Another year, the card was a snowglobe: her family posing in front of the Space Needle (this was in their, and our, Seattle days), with a small plastic zipper bag containing glitter "snow" somehow attached to it; the recipient put a little water in the bag and presto! A favorite of mine was the year she was pregnant with their first child; she wrapped a strand of white Christmas lights around her very pregnant belly and had her husband take a black and white picture of just that, then "colorized" (by hand - this was pre-Photo Shop-in-the-home) just the area of the glow. Beautiful! I aspire to her standards but have no hope of reaching them. Her cards are one of many things I look forward to at Christmas. Heaven help me if she ever decides it's too much work and hits Hallmark instead...

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

Life and death in San Quentin

[w]itnesses at [his] trial said he boasted about the killings, stating "You should have heard the way he sounded when I shot him." Williams then made a growling noise and laughed for five to six minutes, according to the transcript that the governor referenced in his denial of clemency.

Evidence against him included "testimony from two of Williams' accomplices, ballistics evidence linking Williams' shotgun to the murders and testimony from four people that Williams had at different times confessed to one or both murders."

I am, as anyone reading this blog at the time of Terry Schindler Schiavo's death can see, a proponent of life even if the life in question has little or no apparent objective value. Life is precious and irreplaceable. That said, it does not follow that all life must be preserved at all costs. There are reasons to give up one's own life; there are reasons to take a life. My belief in the value of human life wouldn't make me hesitate for one second to kill (or, more likely, to try to kill - it's not something I have practice in) someone threatening my kids, for instance. It's also why I remain reluctantly on the side of maintaining a limited legal status for abortion, though I would like to see its limitations include (a) state-by-state decisions (that is, a rollback of Roe v. Wade) and (b) first-trimester legality only, except in cases where multiple, independent, "blind" reviews indicate that the mother's life, not simply her "health," are in danger if the pregnancy is allowed to continue. This is my personal wish list. I'm not at all satisfied with it, but there it stands for the moment.

Similarly, I recognize that the death penalty opens the door for innocent people to die. More broadly, any reasonable system of jurisprudence - that is, any system that allows evidence other than multiple unambivalent eye-witness accounts coupled with incontrovertible forensic evidence, for instance - opens the door for innocent people to be punished for crimes they didn't commit. The death penalty is more a symptom of that fact than a cause in itself. Such Has It Always Been. I believe there should be a very high standard of evidence for capital cases - of evidence rather than of legal argument; I don't like the thought of clearly guilty murderers "getting off on a technicality" (who does?). Mr. Williams, having been convicted on strong evidence of four cold-blooded murders, died today because his life is forfeit for those innocent lives, regardless of his later redemption (which did not include remorse, since he maintained all along that he was innocent himself).

All right. I have heard the argument that since Williams was a cofounder of the Crips, even if he was innocent of these four murders, he was certainly guilty of conspiracy to murder, that being one of the Crips' hobbies, and therefore deserved to die anyway. I can't buy that. What I do buy is that his original trial, with fresh and clear evidence including his own boasts, came to a just conclusion, and he deserved to die because he was guilty of what he was accused of.

A life has been ended at the hands of society. That life had intrinsic worth from beginning to end, but its owner freely chose to set his life in trade for some momentary pleasure or gratification or perceived need that resulted in four violent deaths at his hands. We have soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan who are setting their lives in trade for a chance at freedom and prosperity for millions of strangers abroad, and for the long-term safety of millions of strangers and a smaller number of loved ones at home. Their trade is a generous act; his was a selfish one. Their trade preserves and defends other lives; his ended at least four. Just as these soldiers choose their course with their eyes wide open, he apparently made that choice years ago, and just as some of these soldiers will have to give their lives in the trade they endorsed, he has given his. Life is precious, but it is not always paramount.

Monday, November 21, 2005

Cult of the child

Look. I'm a mother. I have two sons and a daughter who will one day have to decide whether to serve in this country's armed forces. I don't want any of them to die - in action or any other way; if I had it in my power, they would live happily ever after. But I don't have it in my power. What's more, I know that at some point, the direction of their lives becomes their direction, not mine.

Years ago, I read somewhere about the "cult of the child," a piece of Victoriana wherein childhood, formerly the pre-adult stage of life to which no one paid much attention, suddenly became a kind of ideal state which parents were encouraged to prolong and celebrate. The cult of the child has reached fruition in our time - insofar as anything childish can bear fruit, which is sort of my point. Adults build; adults create; adults contemplate; adults forge bonds. Children imitate adults in doing these things, so that they can learn to be adults. This process is called socialization, or "growing up." But for some of us, apparently, watching our children grow up is too painful to bear. Is it the signal of our own mortality that shakes us? The sense that they may pass us by - or not achieve even what we have achieved? Is it that we're afraid of what they may say or think about us as parents?

I'm not immune to these fears. My husband, a more level-headed and cool-tempered soul than I, reminds me sometimes that we've had our own criticisms of our parents, yet (a) we turned out pretty darn well and (b) we still love our parents in spite of their failings. He intends that these things should comfort me; of course, they just make me more nervous. But that's my problem.

Cindy Sheehan's is apparently that her honored son never grew up to her. How can anyone "support the troops" without acknowledging their agency? How can anyone miss or ignore the fact that they're not just "mothers' sons" but men, entitled in our society to vote, drive, enter into marriage and other contracts, commit crimes and be tried and punished as adults, and - not incidentally - volunteer to serve in the armed forces? They may have any motive they please for their service. Some, probably many, do it for the money or the benefits; these are not trivial, particularly when the starting point is less than zero. Some do it for the adventure. Some do it for the guns; others to get away from home. Some do it for love and respect.

A few, I'm guessing, do it for patriotism and duty, but nearly all will eventually feel these rather abstract impulses, once they've been exposed to them and shown what they mean. Yet military recruiters regularly take verbal fire for emphasizing the reasons that young men (especially young men) do apply, like the education, training, and steady pay, not to mention the chance to do something exciting and dangerous, rather than the small-but-present risk of death or injury in tandem with the only "acceptable" motive: patriotism. Only those who feel, out of the box, an urge to uphold and defend the Constitution of the United States need apply...

The weak-minded pacifism of some of this age's women, and the womanish men who admire them - bah! Do they honestly believe that war is never the answer, no matter what the question? What would their answer have been to Pol Pot? Khan? Vlad the Impaler? A stern talking-to? Shunning? They have avoided stating an answer because the extent of their "vision," such as it is, is to stand in the way of war, to protect all those mothers' sons out there without regard to the cost to other mothers' sons and daughters, including their own children's. They feel good about their efforts - they are serious, they are doing something that matters - but when they unbelievably succeed in snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, they drop the issue like a toy they're bored with and move on to the next war.

There's always a next war.

And what was their answer to Saddam Hussein, benevolent ruler of the Kite-Flying ParadiseTM? Oh yes: authorizing the President to use force to bring him to task, then scolding the President for using force to bring him to task and claiming that the President had pulled the wool over their eyes. This same President whom they've derided for years as too stupid to pound sand: now he was canny enough to fool them in all their august sobriety. This is a reelection strategy?

Apologies to whoever said this first - I can't recall where I read it recently but I had the same thought: "We're stupider than Bush" doesn't have much bumper-sticker value.

Saturday, November 19, 2005

In fervent thanksgiving

My husband immediately made plans to fly to California to be with him and their mother, and my second fervent thanksgiving is for frequent flyer miles; he was able to get on a flight early this morning for the mere cost of 37,500 miles and fifty bucks, even though it's the weekend before Thanksgiving.

When I called my sister for prayer support, she pointed out that she and her husband live perhaps five minutes from the hospital where my brother-in-law was - a fact I'd entirely forgotten as I concentrated on getting the husband across country and communicating with the mother-in-law in transit from SoCal northward. So my third fervent thanksgiving is for my sister and brother-in-law, who are picking my husband up at the airport, giving him a place to sleep very close to where he'll be needed, and performing whatever fetch-and-carry services anyone in my in-laws' family needs, in addition to continually lifting up my dear brother-in-law in prayer - something at which they're better than I am, though I'm doing my best today.

We got through to the ICU eventually and discovered that he was showing good improvement - had been conscious, responsive, able to follow directions and to move his extremities. So, my fervent thanksgiving for the first good news we'd had, and for the ability to put my mother-in-law's mind a little at rest, since she'd been driving through the mountains and unable to receive an update for a couple of hours. And then, a few hours later, just before hitting the sack, we called again and were told he'd shown "massive" improvement - was, in fact, very impatient to have his ventilator removed, though that won't be done for a couple of days since his frequent periods of deep sleep are still too deep for his breathing reflex to function reliably. I fervently thank God for this improvement.

Penultimately, my fervent thanksgiving for the people who stayed with him in the hospital, his estranged girlfriend's parents. They've acted as parents to him during a terrible time and, in spite of their not being permitted to have much information about him since they're not relatives, have apparently been his advocates and companions for many hours since the accident happened.

And finally, I most fervently thank God for the staff of Sutter Memorial Roseville, who saved his life and continue to care for him with kindness and dedication.

One non-thankful note. I second my mother-in-law's exasperated statement, once she'd learned that he was doing much better: "This is the third time I've had to rush to the hospital in a mad panic over skateboarding - I'm going to burn that thing!" I have nothing against skating or skaters, but this is the worst one yet for my brother-in-law. On the other hand, maybe it is a thankful note: my kids are now "scared straight" about wearing helmets, at least for the moment. Whether a helmet would have helped him, I don't know yet, but I've never yet heard of a case in which someone was harmed by wearing one.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Ain't gonna study torture no more

1. I don't think terrorists are necessarily writing anonymous letters to American senators encouraging them to support the Amendment, and

2. I'm about as sick of NIMBY attitudes as I can be.

As to the first. There's much talk, from the "con" side of the Amendment debate, about how if it passes terrorists will have a big party to celebrate that fact that they'll never be tortured if captured by Americans, and will immediately revamp their training regime to take into account the very limited interrogation options available to the American military. But there's extraordinary rendition, the practice of sending prisoners to other nations to be interrogated there. Rendition was a Clinton-era invention (at least officially - I have to wonder how often it happened sub rosa before then), and would not be affected by the McCain Amendment. So terrorists would not face American interrogators with bright lights, loud music, coercive suggestions... instead they might face a well-equipped Saudi, an angry Kurd with access to electricity - who knows? If I were a terrorist, I don't think I'd be happy that the Americans would no longer be my interrogators if I were captured.

(Please note: I do not mean to suggest that either Saudis or Kurds necessarily use torture - just that their rules would be different from ours, as indeed they are now, and there's no Saudi or Kurd or Russian or Somali McCain, for instance.)

Some of Wretchard's commenters opined that we'd start taking fewer prisoners on the battlefield. I doubt it. Our need for intelligence would be as great as it is now. Here I step off into a world of my own devise: if I were in charge of battlefield prisoners, I would try to sort out the intelligence wheat from the chaff as quickly and efficiently as possible - exactly how is an exercise I must leave to the student, since I think it must rely on local informants, overheard chatter among prisoners, intelligence already in hand, etc., but I can't know for sure how it's currently being done. Having discerned which prisoners would be most likely to give important information, I would concentrate my interrogation resources on that fraction. The other prisoners' primary hazard might be death by boredom.

In a post-McCain world, if I just killed every fighter on the field, I would lose whatever intelligence I stood to gain before, so that choice is not open to me - having prisoners is highly inconvenient and expensive, but the tradeoff in intelligence makes it necessary. So I'd still have to take prisoners. Having taken them, I'd still have to sort out who might have useful intelligence, presumably by the same methods I was using before. Then I'd render the useful ones to allies for interrogation, and wait for the results. Finis.

This is a NIMBY argument - "not in my backyard," for anyone who didn't live through the '80s. The scruples of Californians about being able to see offshore drilling rigs does not obviate their existence elsewhere, and if it's an environmental tragedy to have them at all (which it's not - tankers spill far more (and often refined, a.k.a. more toxic) petroleum), it's a tragedy whether they're off the coast of Santa Barbara or Galveston. The immorality of NIMBY is why I am against the McCain amendment: I would rather have combatant prisoners in the hands of American interrogators, who are guided by social and cultural norms that preclude the most heinous forms of torture and seriously circumscribe interrogation techniques, than have squeaky-clean collective hands but know that others were up to their elbows in filth on our behalf.

An analogy to the Catholic Church might be appropriate here. The Catholic Church's guilt in the recent spate of pederast-priest claims, investigations, and convictions is not that the church as a whole was participating in the appalling behavior, but that the Church knew about and enabled the behavior. In what way would the American government - the American psyche - be innocent of torture if we knowingly sent our prisoners to places where human life and dignity are cheaper than we hold them?

Make no mistake, we're using rendition now. I'm deeply conflicted about it. Only long after the fact will we, the public, know whether the intelligence gained by other nations using techniques we refuse to apply was worth the moral cost to us (the moral cost to other nations is, I believe, appropriately their own concern, and that's not just an expedient view of mine). I hope that our government has already performed that calculation, using information not yet declassified, and that it's the demostrated benefit of rendition that is causing us to maintain the policy on a lesser-evil basis.

The bottom line, for me, is that we could outlaw torture in the same way that the Right-Thinking Nations of the World once outlawed war. And it'll be just as effective. Oddly, the traditionally conservative view of humanity as fundamentally flawed, and the traditionally liberal view of humanity as fundamentally good, flip-flop here: I, a conservative, believe that keeping prisoners in American hands, without the stringent limits on interrogataion the McCain Amendment would impose, is far less likely to result in egregious torture than the uptick in extraordinary rendition we'd see if the Amendment passed, because America is fundamentally good. My opponents take the view that the American military must be restrained by force of law from doing what their fundamentally bad natures would lead them to.

Funny.

Friday, November 11, 2005

Happy Veterans' Day!

And that's all I have to say about that.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

Be still my heart!

If you don't know him, for heaven's sake, google him; he's... he's... He defies explanation, that's what. He took a hiatus of - oh, over a year, certainly, for reasons having to do with his health in conjunction with the stresses of blogging. Apparently picked nits wearied him to the point that he lost the energy of spirit needed to stay on the daily treadmill, which I suppose one could view as oversensitivity or prima donnism (to coin a phrase), but I'll take the man's word that his unspecified condition, and the medication necessary for him to blog at a high level, created (and no doubt still create) pressures on him that most of us don't have to face.

But he's back, on his own schedule, at RedState, and I feel like a kid who didn't reach her teens until after the Beatles broke up - only to learn that they'd reunited and were coming to her town!

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

Revolutions and insurrections

All right, that's not entirely accurate; I've been thinking for a few days, since about Day 7 or 8 of rioting, about the tendency among some Americans to call karma on the French and to puff out our collective chest about how such things could never happen here. Seems to me that if a group ethnically representative of twenty percent of your population decides to rise up, take up arms, and attack the infrastructure (thankfully, not the innocent citizenry so far), even a country like the United States would be hard-pressed to retake control. Of course, the French government hasn't done itself any favors by not doing anything substantive for twelve days.

Josh Trevino's blog entry "Twelfth Night," which I just found, has a terrific roundup of recent events. (Apologies to Josh for not taking the time at this moment to find the tilde sign that ought to appear over his "n.") One point on which I think I differ with Josh is that the "French assimilation model" may have failed. He points out, correctly I think, that if this soundbyte of a statement takes hold, the ideal of French assimilation may be discarded, in France and elsewhere. The ideal of which he speaks is twofold: "equality of citizens as citizens, and the primacy of French culture and Western values." The problem I have with the idea is that the French assimilation model, like Communism according to the Left, hasn't really been tried. I'm not as well informed as I'd like to be on this subject, but I understand that the French have not exactly encouraged full assimilation (any more than this generation's Muslim immigrants have sought it), instead making it clear that new immigrants are not quite up to par and can't become so. I haven't heard that there's a by-your-bootstraps mythos in France as there is in the U.S.; this lack of a story to inspire the children of immigrants would certainly add to the alienation of Muslims living in not only sanctioned but informally required ghettoes (in the term's original sense).

In any event, my thoughts turn to various possible parallels suggested by Wretchard's erudite readers: that the American revolution began as a tax protest, the Civil War as a states'-rights debate, and so on. Many commenters wondered whether this French disaster might finally awaken Europe, one calling it "France's Pearl Harbor." And then, one commenter stated as certainty that success in Iraq would cause all the Muslim dominoes to fall, bringing hope and prosperity to people whose only prior alternatives were surrender or religious fanaticism. Here's where I jump off the bandwagon.

We may - I think we will - succeed in Iraq. Iraq will stand proudly as the Islamic world's flagship representative government, and will prosper. But it does not follow that the Bush Doctrine is a sure bet. The American revolution succeeded, against dreadful odds, and the American experiment in liberty and equality has succeeded as well, brilliantly. But its French counterpart, only a few years behind, with the American example to guide it and inspired by the same ideas, thinkers, and emotions, has been limping along for two hundred-plus years with only occasional intimations of success, by comparison. The U.S. shed blood and bitter tears in our Civil War, but recovered and surpassed its previous strength, conviction, and achievements. France's history since its Revolution sounds terrifying to me: the Terror, Robespierre, the weirdness that was Napoleon's empire, the Dreyfus affair and its overtones of anti-Semitism, the trenches of WWI, the Vichy and the Resistance, some members of which were Marxists hoping to win France for their own. The U.S. had the advantage of physical isolation and a second, tremendous advantage in natural resources (there's a reason we've never been a big colonial power) - but that's my whole point: because a radical idea works in one place does not mean it will work in another.

It's a time for nail-biting, not hubristic chortles or triumphalism. We could experience our own spreading urban riots, and if we do we'll discover whether we've actually paid attention these last two weeks. The Middle East may not view Iraq as a beacon of hope, but a Q'ran on fire, and we'll see whether the Iraqis have the stomach to face their coreligionists without conceding. We're experiencing the Chinese curse, "May you live in interesting times." I thank my lucky stars that, up to now anyway, I'm not living in the literal midst of them.

Thursday, October 27, 2005

Bayou of tears

But did you see those Astros? They were swept, but in stark contrast to what one of my son's classmates said about them ("They're sheer losers, dude!"), they made the Sox dig for every out and every run and every inning and every one of the four games that constituted this incredible Series. Game 2 tied up at the middle of the ninth, the Sox forced to fall back on their homefield advantage? A fourteen-inning Game 3? Seven shut-out innings in Game 4? I don't even follow baseball with any degree of devotion, but it was a great run for the Astros, as hard as it was for me to watch. (I'm an inveterate fan of the underdog, plus my family firmly believed in the "McArdle curse," which required us to leave any Cardinals game we were attending back when we lived across the river from St. Louis or risk costing the Redbirds a victory.)

Backe's pitching last night seemed to improve (from darn good to great, I should point out - what a slider he's got!) as he closed in on 100 pitches; why they took him out when they did, I don't know - he still hadn't walked anyone, though it was late at night and I didn't take note of how many pitches he was throwing per inning or how many hits or would-be hits the White Sox were hitting off him in the 7th versus the 2nd. Ensberg's stance is the weirdest thing I've ever seen on a baseball diamond, and clearly it ain't working for him, so I hope he closes it the heck up. I never did figure out the beard thing, but it made it quite a trick for me to tell the boys apart; never mind, they all looked pretty good with it. And finally, I sincerely hope that going almost all the way this year, when they had no right nor reason to expect it, will give them the gumption to take it that last step next fall.

Baseball is, to me, the best spectator sport there is. The action is easy to follow and frequently concentrated in one relatively small area; unlike football and basketball, where your seats - no matter how "good" - will yield bad views for a major portion of the game, in baseball, for the most part you know what you're getting when you buy your ticket. The strategy is accessible on levels from beginner to super-genius. Its pace is neither frenetic nor the hesitation waltz you get in football. It relies not on size or strength (recent emphasis on beefy sluggers notwithstanding) but on a magical arm or winged feet or stunning reflexes or glue in the glove, or two or more of these, and, as with a decathlete, a baseball star can be less than the best in any area and still be The Best thanks to his concatenation of traits. There's almost never blood, almost never a broken bone, yet there are opportunities to "take it for the team" by slamming into a wall in pursuit of the potential home run or by diving face-first for the plate, or, as Backe demonstrated last night, by blocking a line drive with your tender, unpadded flesh and then, without pause, picking up the ball and throwing the batter out at first - you can be a hero without risking a coma or a snapped neck.

And it makes great movies. We picked a good game as our national pastime. And that's all I have to say about that.

Tuesday, October 25, 2005

Oh, Jane...

Me, I'm not about to. If there were a law about how presidents had to make decisions, we wouldn't need presidents, and we'd have rule by committee. If Bush makes mistakes, they're on his own head - and in contrast to some of his forebears, he at least tends not to try to save face by repudiating those who advised him. As I said during the election season, there was absolutely no reason for Bush to yield to Democrats' calls to "admit his mistakes"; it would only have damaged his reelection prospects, provided aid and comfort to the enemy both foreign and domestic, and weakened the confidence of his supporters. The only important factor is whether he corrects those mistakes that actually turn out to have been mistakes. (That is, one side of the political spectrum's claiming that an action has been a mistake ought to be insufficient cause for a president - any president - to take action beyond assessing whether the claimed mistake really is one.) Public confession is a non sequitur.

We elect our executives to bear the crushing weight of a responsibility the likes of which was undreamt of even by Caesar; we age them, kill some of them in office, and I'm certain cost them sleep for the rest of their lives if they do survive their terms. Second-guessing them is our right, but history is long and memory is short; we'd be wise to be sure that our critiques are valid before we go assigning them staggering importance. Like this: was it stupid to have inappropriate relations with a very young intern in the Oval Office? Yes, but not a matter of national security. Was it stupid to nominate Harriet Meirs to take O'Connors's seat on the Supreme Court? We don't know yet, though many legal and/or conservative scholars and commenters appear to think it was an unnecessary risk; it's a question I'd rather learn more about before declaring it so.

Was it wrong to attempt regime change and democratization of Iraq? Seems to me that those who claim it was are not looking very hard at even the proximate effects. If they base their claim on their memory of how the White House "sold" the war (there's always a lot of outraged finger-in-the-face about "This war was sold!" as if any war at any time has been thoughtfully debated in the public square and a plebiscite taken before war was declared), it's a selective memory. I definitely lean toward the "emphatically not a mistake" side, though I recognize that failure and/or unintended consequences are always possible. In those events, as always, we'll have to respond as they come up.

Here's a great tidbit about disagreement within presidential cabinets:

According to John Quincy Adams, at one cabinet meeting late in the Monroe administration Treasury Secretary William Crawford called the president a "damned infernal old scoundrel" and "raised his cane, as if in the attitude to strike." For his part, Monroe "seized the tongs of the fireplace in self defense, applied a retaliatory epithet to Crawford, and told him he would immediately ring for servants and turn him out of the house."

It has little if anything to do with the subject at hand, but it's funny.

Friday, September 30, 2005

"It's fun to share!"

I am tired, so very tired, of children's television programming that attempts to convince children (who are not stupid, just uneducated) that doing the right thing is more fun than doing the thing they want to do.

I've found one short program on Disney that violates this apparently otherwise-inviolable rule: Captain Carlos. In CC, a young boy is hungry. He has some healthful (mistakenly termed "healthy," but that's a post for another day) snack or meal in front of him, but his little sister, who's in league with the Devil, tempts him with junk food. Carlos, however, makes the right choice... and the narrator actually points out that (for example) "Cookies may taste good, but they aren't so good for you" as Carlos scarfs his vegetable soup. It's not very compelling as television, but it has the virtue of being truthful...

...which "It's fun to share!" does not. It's not fun to share when you're three. And it's not fun to take off your shoes in airports when you're thirty-three, or forty-three, or however old the commenter gmat at 6:44 on this post at Belmont Club may be. gmat said, among other things, "The fact is, four years after 9/11, it is still more dangerous, even in Iraq, let alone the rest of the arab world, to be pro-American than to be anti-american. And I'm still taking my shoes off in airports," which might lead us to believe that our goal in Iraq was to feel better rather than to do what we believe is right. As it happens, the United States shares with every other sovereign nation the right (in its first sense) to do what it perceives is right (in its second sense - or I may have these definitions switched) for itself; and as it happens, what we are doing there is also what is right in a sense beyond our own national considerations. We are not acting to oppress; we are acting to create a pied-a-terre for freedom of the individual in a place where that freedom has controlled very little real estate.

The other night I was (again) asking my husband the eternal question, "Do these people actually believe what they say, or are they just saying it because it furthers their agenda in some way?" To wit, does Rangel really believe that Bush is this decade's Bull Connor? I understand he later "clarified" his statement by saying that he meant that "Mr. Bush, like Connor, had become a rallying point for America's blacks." Is that a clarification or a backpedaling? Or merely an acknowledgment that the most vocal sectors of the American black community have lost all sense of history? (I leave aside Major Owens's "'even more diabolical' than Connor" response to Republican requests that Democrats reject the statement).

Does Michael Moore really believe, as he said in spring 2004, that suicide- and car-bombers in Iraq are that nation's "Minutemen"? Or does he believe, as he says in his latest "Mike's Letter," that they're the terrorists we've known them for all along- "Our vulnerability is not just about dealing with terrorists or natural disasters" - when his purpose is to lambast Bush for appointing Brown to head FEMA?

And how about Hillary Clinton? Can we make sense of her recent statement at a Washington protest rally, that "we need to break our addiction to foreign oil" by remaining "absolutely firm in our opposition" to drilling in the ANWR? Her solution to the obvious conundrum contained therein: "The answer to our energy challenge does not lie under the plains of the arctic refuge, but in the minds that are ingenious in America." Relying on the appearance of sudden inspiration hardly seems reality-based, much less a point of national policy. In the interim, in these times before hydrogen can be produced economically, before the tremendous and so far insuperable problem of energy storage at least as efficient as that represented by a gas tank has been solved, how else can we wean ourselves from foreign oil besides by producing more oil domestically?

Again, probably a post for another day. For now, let me stand up and say, "Vegetables do not taste as good as chocolate. Doing homework before playing with friends is a complete bore. And it is not 'fun' to share. But some things we do because they're right." One such thing: not scrambling out of Iraq ahead of an election cycle, nor gauging either the importance or the success of our actions there by how popular those actions are.

Thursday, September 08, 2005

"Affirm the knight"

Recently they gave me a book called Why Gender Matters by Leonard Sax. As I have with so many parenting books I've received over my parenting years so far, I thanked them and put it on the shelf - until last night, when I was fresh out of new reading material and needed something, anything, to put me to sleep.

That book was not the right choice. It scared the bejeebers out of me: I railed against the mismatch between kindergarten teachers and their boy students (virtually all K teachers are women and have been trained to do things like speak gently and encourage kids to use lots of color and to draw human figures; boys physically do not hear as well as girls, and their retinas have more "motion-detecting" cells and fewer "identification" cells, such that they tend to draw relatively monochrome pictures of things in motion rather than nice families in their pretty gardens). I boggled at the difficulties of keeping boys interested in art and music, the girls in athletics, math, and science, when a "gender-neutral" approach is the norm. The chapter on teenage sexuality was so horrifying that when I finally fell asleep, it was with my "self-esteem script" for my daughter running through my head. I'm shuddering right now. As Dr. Sax terms it, the teen sex paradigm has changed from the female to the male: even as recently as ten years ago, the female paradigm was more common, in which the girl demanded, and got, at least a verbal and time commitment from the boy before she'd have sex with him (and of course this was back in the day when "having sex" included oral sex, which this book scarily informs me is now "second base" or "equivalent to kissing" to today's teens). The new male paradigm is, as my husband said this morning, a teenage boy's dream: sex with not only no explicit or implied commitment but actually designed and planned to mean a lack of commitment. "Hooking up." Fear it, if you're a parent.

Fear it for your daughters because any fool knows that it isn't all that fun for a girl or woman to perform sexual acts on a boy or man who doesn't give a tinker's damn about her. Fear it for your sons because this is all the warm-up they get in the desperately important "finding a surrogate mother" sweepstakes - let's face it, wives, that's what we are in one vital respect: we are typically our husbands' only truly intimate emotional connection and support besides their moms. And as Dr. Sax points out, single heterosexual men are sicker, unhappier, and shorter-lived than their counterparts with wives or partners.

I'm perhaps halfway through the book so far, and am growing increasingly nervous about the next ten or fifteen years with these kids of ours. How do we teach our daughter that she's "above rubies" and need not "drop to the broadloom" in Mark Steyn's humorous formulation for anyone unless she gets what she wants - love - beforehand? How do we socialize our sons, foster young men who respect women and have an appropriate outlet for their natural aggression?

As one guidance counselor says in the book, you may not be able to turn a bully into a flower child, but you can turn a bully into a knight. Affirm the knight, she says. I'd add that you may not be able to turn a flower child into a truck driver, but you can turn a flower child into an emotional Rock of Gibraltar for all around her.

I want my sons to be manly, my daughter to be womanly. I want them to have courage, to know when it's time to stand up and be counted, to feel deeply but to know when their feelings are not the most important factor. How can I affirm the knight in my sons? I sure hope there are some answers later in the book, because my confidence is at an all-time low right now.

On the other hand, there's this story, courtesy of Instapundit:

When their homes began to sink in Katrina's floodwaters, elders in the quarter here known as Uptown gathered their neighbors to seek refuge at the Samuel J. Green Charter School, the local toughs included.

But when the thugs started vandalizing the place - wielding guns and breaking into vending machines - Vance Anthion put them out, literally tossing them into the fetid waters. Anthion stayed awake at night after that, protecting the inhabitants of the school from looters or worse.

...

In the days after the storm, the Samuel J. Green school also served as their base for helping others in the neighborhood.

They waded through filthy water to bring elderly homebound neighbors bowls of soup, bread and drinks. They helped the old and the sick to the school rooftop, so the Coast Guard could pluck them to safety by helicopter - 18 people in all.

The knight was in the ascendant at that school. There's hope.

Thursday, September 01, 2005

For the love of God

So instead I'm sending an appeal: for the love of God, for the love of humanity, please don't use this. Don't use this awful tragedy as a smackdown of your favorite Bozo-the-Clown doll. There's plenty of blame, too much blame, to go around: the city and state governments failed their citizenry, some of the citizenry did incredibly foolish things and may cost others their lives, and still other portions of the citizenry are now behaving like rabid dogs and armed two-year-olds, making the horror more horrible. There is no need to begin the accusations so soon. Let's bury the dead first, and pump out the bitter water, and tend to people's hurts. And let's learn: let's learn how to prepare for a foreseeable catastrophe, and how to help others caught up in it. Please. For the love of God.

Thursday, August 25, 2005

Buck up, little soldiers!

He's right, of course. We have nothing to fear but our own flagging spirits. So here are some tidbits to counteract the loudest voices. First, credit where due: I found many of the following at Instapundit, and will credit his permalinks as well as original-source links.

- Instapundit brings a tale of two armors to our attention: An Army colonel tells the NWTimes a good-news story about how the Army is ahead of the curve, and the insurgents, on up-armoring its personnel, starting to equip them with armor that protects against not just ordinary rifle bullets but even against most armor-piercing rounds that insurgents are not yet using, and the August 14 Times reports, "For the second time since the Iraq war began, the Pentagon is struggling to replace body armor that is failing to protect American troops from the most lethal attacks of insurgents."

- When Today's Matt Lauer unexpectedly traveled to Iraq to interview some of the troops, he was shocked to find that their morale is high. Why, he asked? How can it be? The interviewee responded, "Well sir, I'd tell you, if I got my news from the newspapers I'd be pretty depressed as well."

- Are you concerned about Iraq's draft constitution? There are at least two ways to view its language: as one of the (two) most liberal constitutions in the Arab world, Afghanistan's being the other one with substantially identical language, or, more cynically, as a meaningless piece of paper that will be no more adhered to than the old Soviet Union's. A third way of viewing it is that it unequivocally establishes an Islamic state ruled by shari'a in which no woman will ever again feel sunlight on her hair or step outside without a family escort/chaperone. But that way would be self-deceiving. (Naturally middle ground is possible... but it's not the ground on which the American mainstream media are standing.)

- The dreaded IEDs: a historical perspective.

- And two from Powerline: on casualties and the intrinsic risks of soldiering, and on the President's speech yesterday to the Idaho National Guard.

On the off-chance that a reader from the left happens on this entry, please be assured that I've got a million of 'em.

Wednesday, August 10, 2005

Sticks and stones

This exchange was by email, so of course all those limitations took their toll: no body language, no facial expressions, a lag between statement and response, the constant danger of misunderstanding caused by inarticulateness. Apparently she suddenly saw me as a Know-Nothing, an ignorant American (she is married to a Briton), an ideological isolationist intolerant of other cultures and peoples. Her assumption wounded me deeply; after all, she knew me. How could she discard everything she knew about me in favor of a caricature of her political enemies?

I replied, after I'd had time to cool my jets. What I told her, what I believe today, was this: I already know enough about "why they hate us." It's sufficient for me to know that "they" hate us because of what we are - what we are at our national core. We are an individualistic nation and culture, not submissive to God in the sense that "their" understanding of Islam requires, unwilling to give up our right to make our own moral choices. In order to make them love us, or even simply to stop hating us, we would have to become something other than what we are. And we should not (and I'll fight with whatever weapons I have at my disposal to ensure that we will not) take that step.

Can the radical Islamists pledged to our destruction make the same argument? Is it necessary for them to change what they are in order to live in peace with us, and therefore they fight to keep from changing at their core? The answer depends on how much of "what they are" is "people who cannot tolerate the fact that there are others who don't live by strictest shari'a." It makes no difference to me whether this or that Muslim abides by Islam's narrowest interpretation of its laws. But if it's necessary to one Muslim, or one Muslim nation, to impose shari'a on all others, even all other Muslims, well, that's where my culture trumps my tolerance: the right of the individual to pursue his own destiny, within the limits imposed by not interfering unduly with others doing the same, is much, much more important to me than the "right" of another culture to oppress even its own members, and it would be obscene for us to support such a "right" in the name of multiculturalism or stability. This isn't Kissinger's America.

A faction within Islam is out to destroy us. We are not out to destroy Islam, though there's probably a faction here in the West that would like to. A key difference between our side and "their" side is that the nuts on our side control neither the dialogue nor the guns.

Friday, August 05, 2005

A necessary enterprise

My contribution to home life, however, is vital. And today I'm gonna blog about it. Housework, that is.

First the philosophical basis. We decided after our first child was born, when the Man of the House was also the Man in the House and I was the full-time worker, that the at-home person would do "all" the housework, leaving the at-work person free (or shackled, depending on your point of view) to interact with the child/ren after work. Naturally we soon learned that that division of labor is impractical and needlessly mean to both people. There are housework tasks that I hate but Steve enjoys; likewise there are times when he doesn't want to be overrun with children from the minute he walks in until the final salvo of the bedtime battle. So the way it works out is this: I do the cleaning. I do most of the cooking. I dither about yard work because I hate getting all hot and sweaty. I do the laundry but he usually distributes it and puts ours away (the kids put their own away), because I hate that part. He brings me coffee on the weekends, which is a fine morning ritual. He always offers help with the work to be done in the evenings, and if I want to talk I accept the help, because I'm able to work and talk simultaneously; if I want him to talk, I just ask for company, because he talks with his hands and with full eye contact at all time, which puts a serious crimp in the dishes.

As to the cleaning: may I recommend two diametrically opposed approaches:

- Home Comforts by Cheryl Mendelson, and

- the FLYLady.

Cheryl Mendelson, who is a bit persnickety (not that there's anything wrong with that), undertook to write a housekeeping manual such as would have been on the shelf of any middle-class housewife in England or the United States through, probably, the 1930s or so. She wrote a tome, in fact: the book is Bible-sized and biblical in its scope and detail. She tells how to fold a shirt. She tells how to wash a cutting board, as well as what type of cutting board to buy. She tells how to sweep a floor. She tells how to conquer soap scum on a glass shower door if you've let it get out of hand or if (the favorite Mendelson quote of a good friend of mine) "your cleaner has betrayed your trust." She tells what documents you must save and for how long. She tells how to choose domestic help, and how to avoid the commonest pitfalls in the process. The book is an incredibly useful, highly specific reference for almost every housekeeping question you'll ever have. But in order to do everything her way, you'll need her life: she, her husband, and one school-age child live in a Manhattan apartment.

My situation is somewhat different: three kids, one a toddler, in an embarrassingly big house in what amounts to the country - which means dirt. Dirt on clothes, dirt on floors, dirt in bathtubs, dirt on children. Hence the FLYLady. The FLYLady lives in my world and preaches several important sermons:

- You're not behind - just jump in where you are.

- Even housekeeping done imperfectly blesses the home.

- No whining.

- Do your routines.

- Shine your sink!

That last needs a bit of explanation. The FLYLady exhorts all harried homemakers to start small: clear our your sink every night before you go to bed, and shine it. Just shine your sink - wipe it clean, dry it, and polish it if it needs it, so that when you get up the next day even if the entire rest of the house appears to be teetering on the brink of disastrous collapse, your sink will make you happy. She establishes a number of routines and brooks no dispute about them: a bedtime routine that includes doing something for yourself alone, a morning routine that gets you out of bed and dressed down to the shoes so that you are aware that you're doing a job, a daily routine that takes care of what needs to be taken care of, a weekly routine for keeping the house in general trim, a seasonal routine that rotates through the standard areas of the home, hitting them thoroughly at intervals so that "spring cleaning" is never necessary. I only aspire to her full system, but I shine that sink and I have my routines that I do my best at... so I never hesitate to welcome people in, because the house is never more than a week out of "clean" and seldom more than half an hour out of a reasonable standard of "tidy."

Moving on to my favorite cleaning tools:

- Roomba! He's not the best vacuum cleaner in the world, and certainly not the fastest, but he'll work while I'm not there, he manages to find his docking station and recharge himself most of the time, and he's great fun to watch. (In our house, he's a "he." Some have "she" Roombas, I understand. It's a difference that only matters to another Roomba.) Besides, with three floors' worth of carpet, it's nice to be able to do a decent job on, say, the basement without having to lug the big vacuum downstairs every week. I remember when I was six and my dad told me that by the time I was a grownup every house would have a central vacuum system; from what I understand they really are da bomb, but I'd rather have my upright and my Roomba. Oh, and my DustBuster and my ShopVac. (Do I really have four vacuums?)

- FloorMate. This device is a personal version of the zamboni-like device that drives around shopping malls and airports vacuuming, mopping, and squeegeeing the floor. It looks like an upright vacuum cleaner and it's the least uncomfortable or gross way to clean hard floors that I've found. With constant suction, it wets the floor with clean cleaning solution, scrubs it if you want (you can turn off the brushes if you want to for "delicate" floors, but I figure my family is much harder on our wood floors than a weekly scrubbing with a soft nylon brush), then sucks up most of the water - very nearly all the water if you change one setting with your thumb. This is a boon for people whose children do not heed warnings to "Stay off this wet floor! You might [boom] slip and fall..." There's no bending, no mopping with effluent water, no rinsing, no stinky mop drying in the laundry room or the garage. It's not perfect but it's a heck of a lot easier than the hands-and-knees method propounded by Ms. Mendelson. (I fully acknowledge that only the hands-and-knees approach can get a floor really clean, but even then it's only if you do it absolutely right.)

- Clorox Disinfecting Wipes. I resisted these for about two years after they came on the market; they're expensive, compared to making your own disinfecting solution with a little (super-cheap) bleach and water. But the convenience factor cannot be overstated here. I keep a container in each bathroom and in the kitchen, along with a package of the similar Windex Wipes.

- Electrasol 3 in 1 Tabs with JetDry Powerball. Honestly, what I like most about these is not so much the great job they do; I have yet to notice a significant difference between dishwasher detergents, which has led me to conclude that the dishwasher makes a lot more difference. What I like about them is that you plunk the whole little brick into the dishwasher without regard to which compartment it goes in or whether you got a little distracted and poured in a whole lot more than you needed. As a person who has had four dishwashers over the past five years, I value not having to understand my dishwasher in detail: which compartment is "pre-wash," which is "main wash," will a particular compartment require a particular setting in order to pop open... Feh. Unwrap a little brick and toss it in.

- Clorox ToiletWands. Toilet brushes are gross. This thing is a slim plastic wand that you can hang unobtrusively on the side of your toilet tank, then, when you want to clean the toilet, you click it onto a scrubby disk impregnated with cleaner. When you're done, you hold it over a waste basket, click again, and the scrubby falls into the trash. I have one in each bathroom, together with a six-pack of scrubbies. The Lysol ReadyBrush seems giant by comparison, and though it claims to disinfect its own brush head each time you use it, it still seems gross. The Scrubbing Bubbles flushable toilet brush seems not very scrub-worthy, and with a septic tank I'm pretty sure I shouldn't be flushing things like that in the first place. Scotch-Brite has a competitor out there, but for some reason I like the aesthetics of the Clorox model; you never actually have to pick up even the clean scrubby.

- Lest you think I am a full dues-paying member of the Disposable Society, dishcloths. I buy (once every five years or so) a big pack of cheap washcloths, which I then change out at least daily, washing them in the washing machine with chlorine bleach. Chlorine bleach, which has gotten a bad rap lately and is undoubtedly toxic, is also highly effective at disinfecting. I want my dishcloths clean; the sponge-in-the-dishwasher method seems suspect to me, as interior sponge pores aren't readily exposed to the water and detergent. Evidently microwaving sponges can sanitize them - but be sure all food is off the sponge first.

- Likewise, cleaning cloths for anything involving heavy scrubbing or just a lot of dusting. I use the least expensive cotton napkins I can find; they're lint-free and can be laundered vigorously.

Enough already! I am not a clean freak, I promise. Ask anyone who knows me. I subscribe to the belief that some dirt is not only inevitable but necessary and valuable, and I apply the Five-Second Rule to any food that falls on the floor as long as it's not the floor in front of a toilet or the litter box, for instance. I don't sterilize baby bottles but I do sterilize beer bottles (maybe a homebrewing blog entry some other time); I don't iron children's clothes but I sometimes iron sheets. I am a catch-as-catch-can housekeeper, just doing my best to support the family in the way to which I am currently called.

Friday, July 29, 2005

America the one-eyed

The first [universal adage] is to stay out of land wars in Asia, but only slightly less well-known is this: Never go up against a Sicilian when death is on the line! Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha! [And then he drops dead.]

I have re-created the quote. All who know the movie, please cut slack.

So my first thought is that if, as Wretchard at Belmont suggests, we're poised to enter that realm of military folly known as "land war in Asia," I certainly hope he's right that our now-demonstrated ability to project force far from the sea and from permanent bases will be as effective as the steppe horses were for the Mongols - NOT that I advocate attacking China, of COURSE. Good gravy. But the point is, that's one big swath of land there, Central Asia, and more than one army has wandered around in it for a long time, getting progressively hungrier and colder before reaching its goal. If our fortunes take us there, we'd better have our supply lines locked down and defended...

And my second thought is related. Some Belmont commenters, examining the prospect for our chasing down Osama bin Laden in Pakistan or wherever his fortunes have taken or will take him - but probably northward if, as many believe, he's currently harboring in northwestern Pakistan and we have any success in convincing Musharraf that we're going to come after bin Laden no matter how concerned he, Musharraf, is about Pakistan's border integrity - brought up the question of why we're not trying to get Russia or (less probably) China involved in the forward effort. After all, the reasoning goes, all the 'stans were once in the Soviet sphere and Moscow retains at least illusions that they are Russia's turf; why not use that to our advantage?

The title of this post is intended to convey my belief and understanding that we are not licensed drivers of the engine of history, a tortured metaphor if ever there was one. We, like every other civilization and people before us, are doing the best we can to choose a course that is good for us. The difference between what we're doing and what other, less visionary (if I may use the term) nations are doing is, I think, that we're attempting to see at least the medium term. It's been pointed out in various spots and with various emphases that the War on Terror is in fact in some respects a war for oil - or, more cogently, a war for Our Way of Life, since OWoL runs on oil (and gas, and coal, pace my husband in the energy biz). Oil matters. Oil on the open market matters a lot - nowhere have we "conquered" an oil-producing nation and arrogated its oil resources for ourselves; we always buy, and in practice we prefer the market model for pricing. Giant oil fields in the hands of militant Wahhabists - that's not a scenario we should want to promote, either from an OWoL standpoint or from a human rights standpoint. Central Asia has promise as an oil-producing region - some say as productive a region as the Middle East is today, though I haven't looked that up anywhere. So. Do we want that region under the control of bin Laden's spiritual brethren (by whom I do not mean Muslims, but rather militant Wahhabists, Islamofascists, or choose your euphemism for Muslims who believe that their mission in life is the return of the Caliphate by whatever means necessary)? Clearly not.

But almost as clearly, we don't want those lands under the control of a Russia that apparently still entertains notions of "democracy" radically different from ours. (Recall that the Soviet Union always tried to convince the world that it was a "democracy" too - just a remarkably unified one.) Nor do we want China, with few pretensions to post-Soviet reform, in control. While we're allied with both, in general, in the GWOT, our interests do not align perfectly, to say the least. So in the medium term, at least, it behooves us to prepare to project our power into the vastness of Central Asia, not to subjugate it but to provide its people with an alternative to Chinese central control and Russian pseudo-empire. If we succeed in promoting real democracy in the 'stans, how much the better for us?

This is where I get puzzled: where are the Russians and Chinese? Why aren't they taking advantage of either the wide-openness of the region or our current "distraction" in Iraq? If we must get involved in Central Asia, even if "only" to the extent of supporting democratic reform movements (as we're already doing, which in itself represents a pretty significant departure from the past century or so), we stand to create a region of allies where we've never had them before. If Russia and China have had the use of their eyes over the past twenty years or so, perhaps they've noticed that Soviet-style socialism is gone the way of the dodo and Chinese-style socialism has survived only by hybridizing heavily with capitalism; why would they ignore these facts of recent history and, respectively, warn the US to stay out of the 'stans because they're "traditionally" part of Moscow's sphere of influence, or apparently ignore them altogether? See this map and ask yourself why China isn't in the news all the time concerning Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Certainly there are ethnic considerations - but I say again, these countries appear to be "up for grabs" in the alliance sweepstakes, in an area of important strategic value right now and potentially even more important economic value in the future - especially with China's oil consumption growing like the weeds I can't keep ahead of in the back yard. Yet - nothing. In the country of the blind, we do appear to be king.

Tuesday, July 26, 2005

Do I cheer or weep?

Called "The Same Old, Same Old," the article concerns the circumstances that made the London bombings possible: in particular the feelgood political correctness that declares any suggestion of a gigantic common link between the London bombings, the Egyptian bombing last weekend, Madrid last year, 9/11, the USS Cole, the Marine barracks in Lebanon back in the '80s, and so on, and so forth, ad in-bloody-finitum - a violent and fundamentalist interpretation of Islam - racist and unacceptable. We are so afraid to be insensitive to the cultural imperatives of others, Hanson says, that we shelter the asp in our bosom, trumpeting free speech as young Muslims in London (and not just London) are taught to hate the system that feeds, clothes, shelters, and permits them to hate it.

That's not the part I'm dismayed about. All that is common knowledge among those paying attention. Look, I've got no beef with Islam; as I might say about Christianity if I knew as little about Christ as I know about Mohammed, any religion that can retain the belief of a billion people can't be all bad. (Yes, I know some call Islam the "one-way religion"; I have no personal knowledge of how easy, difficult, or acceptable it is to become an apostate Muslim, so I can't comment.) I have a huge problem with the fact that the Muslim "mainstream" is not more vehement in its denunciations... and this is the part of Hanson's article that I hated. He says this:

...a madrassa that indoctrinates directionless youth, or an imam who shouts hatred to his audience, must always simultaneously when called upon “condemn” terrorism, and then seek victimhood when the rare scrutiny of an outraged public nears.

And even more to my dismay:

Bin Laden has so far only made one mistake: He took down the entire World Trade Center rather than the top floors, and had the misfortune of having George Bush as president. Thus he lost Afghanistan and ended up with democratic reform from Iraq and Lebanon to the Gulf and Egypt. Train bombings in Madrid and bus explosions in London, like the carnage in Iraq, are preferable, since they are enough to terrify and demoralize the Westerner but not quite enough to knock sense into him that only military resistance and victory will save his civilization.

In other words, the goal of terror attacks (brace yourselves, this is self-evident but I forgot it) is terror, not necessarily the infliction of mass casualties and certainly not military supremacy. Hanson suggests that the scale of terror attacks since 9/11 has been deliberate - deliberately small: just enough to sap our will for this fight, without being enough to galvanize our resolve. So far they've failed, because of Bush, Blair, and Howard and the stubborn will of the Anglosphere (not being culturalist here; can anyone believe that if we went home to sulk within our own borders, Romania would fight on?). What happens in 2008?

On the good side, it's not clear on which side the terrorists have been erring: have the attacks been too small to sap our will effectively, or too large such that they have bolstered our cojones? And, too, I confess to a sense that even Hanson can overestimate our opponents: are they - and by "they" I mean the midlevel people who must be in charge of planning and executing attacks such as the London bombings - as subtle as all that? Or would they in fact aim for the most blood, the most torn metal, the most horror they could gin up?

In any event, their second try in London is clearly a loss for them, a win for us. In no way was London "terrorized" by the second, failed bombing attempts. I've heard a few commenters suggest that the failure will act in the terrorists' favor in that they'll garner grossly misplaced sympathy on their account - but really, people. And, too, I've heard some commenters make the point that we tend to ascribe to our enemy almost supernatural powers - their numbers grow magically and geometrically, like the undead fighters in Alexander's Black Cauldron (LOVE those books), while we can't always make our recruitment numbers (but our reinstatement numbers are exceeding goals) even with increasing enlistment bonuses, etc.

All right then. I've cheered myself up to some extent. Kids crying to go to the pool - off I go to brave the chlorine, the ultraviolet, the Lyme disease...

On eating and having cake

There's been a lot of talk from some quarters, including the Kerry camp in the runup to the November 2004 elections, that if Bush had "kept his eye on the ball" (as if that was the problem) and captured bin Laden rather than getting "distracted" by Iraq, we wouldn't now be in the mess those quarters claim we're in. (Side note: this view of how to capture bin Laden reminds me a lot of an old joke about how to perform a do-it-yourself kidney transplant: "First, remove the diseased kidney..." I'm no doubt grossly misstating it, but the point the joke and I are trying to make is that simply glossing over the so-difficult-it-could-be-considered-miraculous-if-successful does not constitute a complete instruction. Thusly: "All Bush had to do was keep his eye on the ball and he would have captured bin Laden.") Anyway. The implication, sometimes the bald statement, was that capturing bin Laden would bring an end to Islamist terror against the West. If that were the case, my goodness, sounds like a global terror network to me...

Friday, July 08, 2005

Saturday, July 02, 2005

The stakes in Iraq

My point was that Republicans and/or conservatives and/or generalized hawks are highly motivated to keep trying to convince those on the other side of the necessity and positive significance of the war in Iraq not just because we're contentious, but more importantly because Bush cannot be reelected. We face the prospect of a Democratic or otherwise dovish White House in the next Presidential term, and if we lose the political will to stay in Iraq until our presence is no longer needed to create or maintain security for the new democratic government there, we stand to lose much more than face. I laid out several results of an Iraq cut-and-run, which are not an exhaustive list but are what I immediately thought of:

If we leave Iraq before it's ready to stand on its own, surrounded by non-democracies and pseudo-democracies and itself a novice at self-determination, we:

1. Squander our hard-won credibility - for once in the past fifty or so years, we've so far done what we said we'd do;

2. Condemn one or more ethic minorities in Iraq to the tender mercies of whatever faction manages to grab power there;

3. Orphan democratic movements throughout the region;

4. Lose out on a big chunk of energy portfolio diversification and put ourselves again in the Saudis' hands;

5. Lose an incredibly valuable intel/translator/interlocutor source and an actual Arab ally;

6. and have to do it all again one day.

One commenter who disagrees with me put it this way:

1. Squander our hard-won credibility - for once in the past fifty or so years, we've so far done what we said we'd do;

I didn’t know we said we would invade a country for what non-state actors were doing to us in Africa, Aden and NYC. “If you hit me again Jamie, I’m going to punch out Cecil!”

We picked out Saddam to overthrow for the acts of others? How does punching out the wrong man strengthen our credibility against the perpetrators? The only way it does is to link terrorists to Saddam, which is why it’s the current R talking point.

2. Condemn one or more ethic minorities in Iraq to the tender mercies of whatever faction manages to grab power there;

This is our job? They have been fighting each other longer than this country has existed. I really don’t think we will “solve” it , or even contain it, unless we maintain a military presence indefinitely. They will have to work it out themselves.

3. Orphan democratic movements throughout the region;

We have adopted them? We are supporting fifth columnists in every Arab country? How would we feel of foreign powers were funding “movements” in this country? Remember the Chinese political fundraising ruckus?

4. Lose out on a big chunk of energy portfolio diversification and put ourselves again in the Saudis' hands;

So you agree it was the oil. We’re the strongest – we’re taking it – right? Law of the jungle. Nasty, brutish and short.

5. Lose an incredibly valuable intel/translator/interlocutor source and an actual Arab ally;

How is a perceived puppet valuable to us in a conflict with our opponents? We’re winning hearts and minds by imposing western values? If “liberals” are traitors for mentioning the word NAZI, how will some Islamic demagogue paint a “free” Iraq?

6. and have to do it all again one day.

Absolutely correct. We will have to do it once a generation – forever.

And below is my reply:

"We resolved then, and we are resolved today, to confront every threat, from any source, that could bring sudden terror and suffering to America" and "Over the years, Iraq has provided safe haven to terrorists such as Abu Nidal, whose terror organization carried out more than 90 terrorist attacks in 20 countries that killed or injured nearly 900 people, including 12 Americans. Iraq has also provided safe haven to Abu Abbas, who was responsible for seizing the Achille Lauro and killing an American passenger. And we know that Iraq is continuing to finance terror and gives assistance to groups that use terrorism to undermine Middle East peace." (both from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2002/10/20021007-8.html) "Saddam Hussein and his sons must leave Iraq within 48 hours. Their refusal to do so will result in military conflict, commenced at a time of our choosing." (from http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/03/20030317-7.html) Our quid-pro-quo was clear; we followed through exactly as we said we would. For more on the ever-popular "Why Iraq? And if Iraq, why not North Korea?" please see den Beste, for example, at http://denbeste.nu/essays/strategic_overview.shtml, for all the good it'll do. Warning: it will give you what you think is ammo for the "Bush lied!" thing; he points out that WMDs were not a primary rationale against Iraq, though their threat was certainly viewed as real.

This nation never said "We will pursue the planners and any surviving perpetrators of the attacks on 9/11 to the ends of the earth - but only those people" because, as many have noted, the criminal-indictment model had already proven itself a big flop. As much as you personally, and many who share your views, would like to believe that our only legitimate action would have been a la the prior WTC garage bombing, the policy of our nation from September 2001 onward was to take the fight to terrorists and their supporters (necessary, since terrorists don't have to squat in one spot and wait, but nations do), at our option rather than solely in response to their actions, wherever we found them.